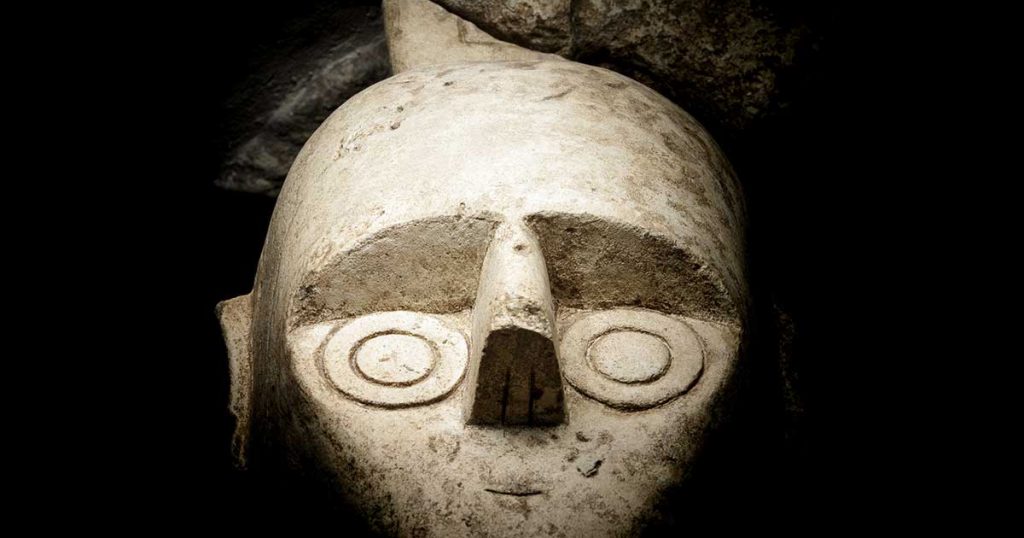

Archaeological site of Mont’e Prama

The site was discovered by chance in March 1974, when ploughing of a field brought to light the first fragments of the statues. From that point on, the site underwent several digging campaigns between 1975 and 1979, 2014, 2015-2016 and, more recently, between 2018 and June 2022, the date of the last intervention.

Today, fieldwork is focused on extending the excavation area to gain a clearer understanding of the organisation of the area and the relationship between the sculptures and the necropolis, and to determine whether a temple or sanctuary once stood there, as well as other structures or buildings having other functions.

A unique necropolis in Sardinia

The early archaeological investigations revealed a complex necropolis in use for several centuries, showing signs of several different periods of development. The area explored has revealed three phases of use, each with a different type of tomb, with progressive restructuring of the site.

First phase

To the east of a road dug out of the soft rock, we find a necropolis perhaps in use from the 11th and 10thcenturies BC, consisting of small single well tombs, shallow and of cylindrical shape, closed by a pile of small stones. Each tomb was meant for a single body, in crouched position, at times with a vase, which was often in pieces.

Second phase

In a second period, probably between the 10th and 9th centuries BC, the local tribes decided to give a monumental aspect to the site: new well tombs were created, completed with stone structures and still grouped in a haphazard manner, each holding one body in crouched position with legs set high. The tombs were covered by a carefully worked stone slab.

The tombs were found by archaeologists to have been heavily damaged due to the deep furrows of ploughing in modern times.

Third phase

In a third phase, probably at the beginning of the 8th century BC, the tombs were excavated in the soft rock and covered with one or two square sandstone slabs. Some are also lined by two vertical slabs on the sides (these are classified as ‘pseudo-cist burials’). These tombs still preserve the original burial, with the body crouched and the head protected by a small slab of limestone. The tombs were lined up along the edge of a funerary road and were separated into groups by vertical slabs set in the ground. Each group of tombs is fenced towards the road by a line of slabs set vertically and is indicated by at least one betyl, a stone pillar in truncated cone shape, which at times exceeds 2 m in height.In this third phase, the necropolis was decorated with a spectacular complex of statues and models of nuraghes in limestone.

We do not know how long the necropolis maintained this distinctive layout.

At the end of the 4th century BC, in the midst of punic domination, the fragmented statues were placed on top of the tombs and along the road.

Right over the necropolis, we therefore find a heap of sculpture fragments, heaped in a disorderly manner together with other objects of material culture such as pottery of the nuragic, punic and roman periods. It is possible that the statues were smashed at that time, perhaps intentionally, but we cannot rule out other times and causes.

Grave goods

The tombs of the third phase are without grave goods. The only exception is tomb 25 where, under the body of a young man, a scarab seal in vitreous white soapstone was found. This object, imported from Egypt, has been dated by comparison between 1130 and 945 BC.

The discovery of oriental grave goods in Nuragic burials is very rare.

This unusual find indicates a process of change in the early Iron Age, and is certainly not easy to interpret.

Further readings:

L’Heroon di Mont’e Prama, Bedini-Tronchetti et alii 2012, pp. 15-23

Mont’e Prama. L’Heroon dei giganti di pietra, Tronchetti 2015

L’Heroon di Mont’e Prama nelle pagine di Giovanni Lilliu, Zucca 2014

Guardiani, dei o eroi? marzo 1974, nel podere di Sisinnio Poddi, presso Cabras, venne alla luce un grosso reperto archeologico. Cominciò così la lunga quanto appassionante vicenda dei giganti di Mont’e Prama, Manunza 2013

La pietra e gli eroi, Minoja e Usai (a cura di), 2011

Interpretare Mont’e Prama: l’heroon, Bernardini 2015, p. 52<

L’Heroon di Mont’e Prama, Zucca 2013

Archaeological site of Mont’e Prama

strada provinciale 7

09072 Cabras (OR)

Closed to the public